In desperation at their impending electoral boot in the arse, the Liberal Party has dredged up, rather ineffectively, it seems, Stephen Harper’s unambiguous support for the 2003 invasion of Iraq. In so doing they not only are busy fudging Paul Martin’s dubious stance on the issue but also perpetrating poppycock that is being swallowed by an ever-increasing proportion of Canada’s apparently amnesiacal population: that is that Jean Chretien was some kind of national and international strongman, a stalwart and defiant bastion against the indisputable bad judgment and bad intentions of our giant southern neighbour’s president.

Waiter: reality check, please! How soon, we forget the weeks of waffling and months of temporization before March 20th, 2003, when Chretien offloaded the dreadful choice at hand onto “international law” as represented by the collection of

do-nothings and bad asses known as the U.N. Security Council. Even NDP leader Jack Layton, in correctly crapping all over Paul Martin’s Iraq credentials, lifts Chretien to Churchillian heights, as a lone and valiant guardian against a gathering military storm. Thus, in a campaign speech supposedly about public transit, Jack careened off course, as he is so inclined, to say: “Mr. Martin is wrapping himself in the courage of his predecessor…”

do-nothings and bad asses known as the U.N. Security Council. Even NDP leader Jack Layton, in correctly crapping all over Paul Martin’s Iraq credentials, lifts Chretien to Churchillian heights, as a lone and valiant guardian against a gathering military storm. Thus, in a campaign speech supposedly about public transit, Jack careened off course, as he is so inclined, to say: “Mr. Martin is wrapping himself in the courage of his predecessor…”Courage? Huh? Or should I say, “Eh?” Have we forgotten both the impoverished rationale for non-engagement and the confusing, shilly-shallying verbiage of that “courageous” predecessor and his foreign affairs minion, Bill Graham? Do we not recall that it was way less than 48 hours before the Yanks struck that Chretien finally announced what Canada’s position was?

The reasoning and the timing reveal anything but courage – or even coherence. One may pore in vain over the reports of the Liberal deliberations and revelations of the time for a lucid statement or position justifying the now commonplace image of a stalwart leader. Did Chrétien ever doubt, let alone dispute the likelihood of WMDs based on Saddam’s earlier liberal use of chemical and biological warfare and the suspicious Osiraq nuclear facility which the Israelis wisely reduced to rubble in 1981? Not at all: indeed, his boy Bill, summing up the basis for Canada’s position to Parliament on the very day of the invasion, mused about why all this had happened:

What then are the lessons that I draw from the past few days? First, I would say that Saddam Hussein acquired weapons of mass destruction. This is clearly what started this and what brought us to where we are.

Chrétien and his coterie no more questioned WMDs than did Bush or Blair at the time. Indeed, at least according to then-Cabinet minister, Sheila Copps, the Prime Minister had a Canadian-style pint-sized brigade all ready to head for Iraq but got talked out of it by herself. Nor did he ever challenge the terrorist connection the Americans asserted, despite the preposterous notion of an alliance between the secular Ba’athists – who routinely included Islamic militants in their murderous swath of repression - and the Wahabi-spouting devotees of Osama?

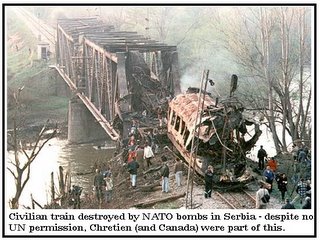

Chretien’s barely intelligible mutterings throughout the long drawn months as Bush and the Brits rattled their sabres, were all about deferring to whatever the U.N. Security Council (not a nicety that Chretien gave two hoots about when Canada was indeed among the most bellicose participants in NATO’s bombing of Serbia).

But this time around, Chretien was ready to jump off any cliff if -- but only if – selected external powers sitting at the Security Council table, said okay. Our much-trumpeted and over-stated national reputation as peacekeepers, indeed any real sovereignty was to be gladly signed over to the say-so of the same clique who fiddled while Rwanda burned, who, now, for two years have dithered about whether the 6-figure killings in Darfur are really genocide and who despite the wordy bluster of Resolution 1441, did little but chatter as Saddam thumbed his nose at weapons inspectors and the world. This is how, and only how, Chretien set his and our nation’s moral compass re the Iraq invasion.

But this time around, Chretien was ready to jump off any cliff if -- but only if – selected external powers sitting at the Security Council table, said okay. Our much-trumpeted and over-stated national reputation as peacekeepers, indeed any real sovereignty was to be gladly signed over to the say-so of the same clique who fiddled while Rwanda burned, who, now, for two years have dithered about whether the 6-figure killings in Darfur are really genocide and who despite the wordy bluster of Resolution 1441, did little but chatter as Saddam thumbed his nose at weapons inspectors and the world. This is how, and only how, Chretien set his and our nation’s moral compass re the Iraq invasion.

Chrétien’s belated, garbled and thinly-justified position on the American adventure was so bafflingly feckless through the long build-up to war, that analysts had to look elsewhere for an explanation. It could not escape notice that, with his licked finger ever to the domestic political wind, Chrétien was closely watching the reaction from notre société distincte, the one that has consistently opposed military action, since Confederation. Old political fox that he was, Chretien could see that the deployment of Canadian troops to full combat would be a gift to the Bloc and their PQ confreres, something he could never stomach.

This was no admirable mighty-mouse stand for Canada against the 800-pound Yankee gorilla, no shining exemplar of international morality,

just quintessential Chretien doing, at the eleventh hour and fifty-ninth minute what any natural born snake-oil man would: play righteous big-shot to the gullible.

just quintessential Chretien doing, at the eleventh hour and fifty-ninth minute what any natural born snake-oil man would: play righteous big-shot to the gullible. And, I suppose, it is further testament to his guile, - not courage - that the myth survives, nay, thrives, of how and why he and his colleagues did what they did amidst March 2003’s “shock and awe”.